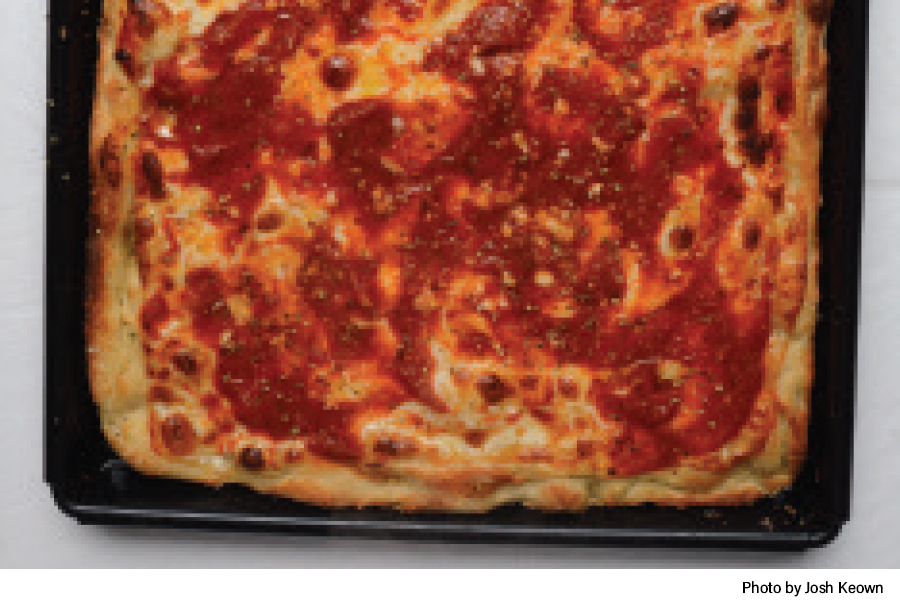

The story of how our Pizza Sauce came to fruition

The Global Tomato Market generates $181.74 Billion in revenue yearly. To put that in perspective, that is larger than the GDP of Ukraine and Morocco, and not far off from Greece, Peru and Portugal. According to a study published from the USDA in 2019, “Americans on average consume 30lbs of tomatoes per year. Sixty percent of that comes from canned tomatoes, as Pizza Sauce contributes to the high consumption of the vegetable.” Here is the story of how our Pizza Sauce came to fruition.

Tomatoes are a central and iconic element to Italian Cuisine, yet they are actually a “newer” ingredient that didn’t come along until the late 1600s. It’s hard to believe that some of the most famous Italians ever, Julius Caesar, Leonardo Da Vinci, Marco Polo, Michelangelo and even Christopher Columbus never had a dish of Spaghetti Pomodoro. George Washington, Ben Franklin, Sam Adams… our Founding Fathers did not know what pizza was.

Hundreds of years ago, long before Europeans had set foot in the New World, tomatoes grew wild in the Andes of Western South America. The natives began cultivating them, eventually bringing the plant northward through Central America and into Mexico. When the Spanish arrived in the early 16th century, they found the inhabitants growing a food crop called “tomatl” in the native language.

Seeds were brought back by the Spaniards, but tomatoes were not an easy product to introduce to fellow Europeans: they did not look or taste like any known plant, they had a strange consistency and texture and they were very acidic when green. Once ripe they were soft and they disintegrated in the lengthy cooking which was common at the time. But the climate and soil of the Mediterranean were ideal for their growing, and since they did not compete with local crops it was used as a supplementary one that did not interfere with the traditional ones.

For many years, tomatoes were feared,

partly due to their resemblance to the venomous nightshade plant and partly because of a false story that quickly circulated about a group of upper-class Europeans who died after eating them. While the group did experience fatalities after consuming tomatoes, further investigation revealed that the high acidity of the tomatoes leached lead from the pewter dinnerware, causing lead poisoning. The story circulated for years, raising suspicions across the continent.

It wasn’t until 1692 that we see the first-ever recipe featuring tomatoes appearing in “Lo Scalco alla Moderna” by Antonio Latini. Antonio, an orphan at the age of 5, grew up homeless in the streets but was eventually taken into a kitchen. He worked his way up to become the Steward for the Viceroy of Spain and Naples. His published recipe was for a sauce containing cooked tomatoes, intended as an accompaniment for cooked meat or fish. In 1790, Roman Chef Francesco Leonardi published the highly regarded cookbook “L’Apicio Moderno”, where he wrote the first recipe and proclaimed he had ”invented” pasta al pomodo (pasta with tomato sauce).

Early traces of pizza go back to ancient times with the Egyptians, Romans and Greeks, but pizza as we know today emerged in the 18th century, in the Southern Italian port city of Naples. From 1700 to 1750 the city’s population doubled from 200,000 to 400,000. There was a big need to feed a bustling metropolis with people always on the go. Street vendors would purchase disc-shaped flatbreads from bakeries and keep them warm in small tinned copper stoves that they balanced on their heads. Ingredients were simple like lard, garlic, salt, basil and in some instances caciocavallo cheese and fresh tomato.

Many believe that pizza sauce was invented by Raffaele Esposito in 1889 because he was credited with the invention of the “Pizza Margherita”. According to the legend, Queen Margherita summoned Raffaele to the Royal Palace to prepare the popular dish among the locals in Naples. Out of the three pizzas he prepared for her Majesty, her favorite was the tomato, basil, mozzarella pizza, of which he named in her honor. However, while we can attribute the naming of the pizza to Raffaele, we know with certainty that he was not the creator of that pizza, nor the first pizzaiolo to use tomato sauce.

In the second half of the 1700s, references to fresh tomatoes as pizza toppings began to emerge in essays and books, reflecting a growing trust among Neapolitans in tomatoes, due to their abundance, low cost, and ease of cultivation. The evolution continued in 1792 when Giuseppe Sorrentino obtained a business license to bake focaccias and pizzas, marking the establishment the first recorded pizzeria in Naples. This shift sparked a wave of entrepreneurs opening pizzerias, breaking away from the reliance of bakeries. Over the subsequent 50 years, Pizzaioli likely engaged in experimentation, incorporating tomatoes and tomato sauce onto pizzas as we recognize them today.

The first factual mention of pizzas with tomato sauce,

specifically describing what we now know as “la marinara” and “La Margherita” comes from Francesco de Boureard in his 1866 book “Usi e costume di Napoli” (Customs and traditions of Naples). We’ve established pizzaioli were making sauces with tomatoes, let’s remember that tomatoes were still seasonal during this period, available only part of the year.

Francesco Cirio, a Northern Italian, started working at his father’s fruit and vegetable stand in Turin at 14. Inspired by French confectioner and chef Nicholas Appert, Cirio established a canning factory in 1856, at the young age of 20, pioneering the Appertization method for preserving food with heat initially focusing on peas. With the high demand of tomatoes in Southern Italy, Francesco founded the countries first tomato factory in 1875, near Naples in San Giovanni Teduccio and Castellamare di Stabia. These towns were near the Vulcanic Angro Sarnese region, where the popular San Marzano tomato continues to grow till this day. The year-round availability marked the exponential growth of tomato popularity in Italy, and then also in Europe. We also know it’s safe to say in 1875 pizzaioli all over Naples were using the peeled tomatoes year-round to make their pizza sauces.

Italian immigrants introduced pizza to New York in the early 1900s.

Initially baked in coal fired (also some wood) bakery ovens, their sauce mirrored traditional methods, made by hand crushing whole peeled canned tomatoes with the addition of salt. The canned tomatoes being used were not the expensive imported Italian ones, but the more economical American grown, which had a different flavor profile than they were accustomed working with. Due to the higher acidity than the San Marzano, I would suspect sugar and olive oil could have begun to find its way to some of the Pizzaiolis recipes, in attempts to achieve the balance of the tomatoes they were accustomed to.

The complete evolution, or revolution depending on how you want to look at it, really began in the 1930s when Frank Mastro invented the gas oven. Adopted by most New York and East Coast pizzerias by the 1940s, these ovens baked at a lower temperature that required much longer cooking times. A sauce with less water content that prevented the pizza from drying out and to help retain its moisture was needed, and so thick tomato sauces, dense purees and slow cooking batches of tomatoes to reduce water content where deployed.

By the 50s pizza had spread rapidly across the country. It was taken up by many enterprising restaurateurs who were often not from an Italian background, and adapted to reflect the tastes and needs of the cultural melting pot that America was becoming. It was no longer an Italian ethnic dish, but a proud food that became symbolic of the local people it was serving. Hence we see the birth of different styles, like the Chicago Deep Dish or the Detroit Pan, and the addition of non-traditional ingredients to their pizza sauce like sugar, oregano, garlic, onion, pepper and rosemary to name a few.

Pizza sauces have not really changed much from the 60s and 70s when we had our biggest boom of pizzeria openings. In talking to many operators around the country, I have noticed places adding their unique signature, like Janet Zapata of Pizza 550 in Loredo, Texas, who adds a little crushed pepper to her sauce to give it a kick, or Tony Garcia from Guy from Italy in Lubbock, Texas, who likes to add a little more sugar than average to kill the acidity and bring an additional level of sweetness. I do believe we will see a change in the way tomatoes and sauces are packaged in the future. Some manufacturers are offering their products in plastic aseptic bags (think bag in box), that they claim offers a unique set or advantages that help preserve the freshness, flavor and nutritional value of tomatoes. And some dispute that claim. Regardless of how it’s packaged, one thing I know for sure is that we will always love our pizza sauce.

Pasquale DiDiana is owner/operator of Bacci Pizzerias in Chicago, Illinois and a frequent speaker at International Pizza Expo.